Fire and Iron - our site & story

Fire and Iron Gallery is based on a 10-acre site that has many facets and many stories to tell.

Visitors to the Gallery often ask about the enigmatic house tucked behind shrubbery just metres away.

Lucy Quinnell’s home ‘Rowhurst’ is a Grade II* Listed Building, and with its noisy neighbour the M25, it recently featured in BBC4’s ‘The Hidden Wilds of the Motorway’. Scenes in the 1960s film ‘Twinky’ were filmed here, and a photograph shows Susan George and Trevor Howard dancing by the fireplace. An episode of ‘Last of the Summer Wine’ featured the adjacent forge, and numerous documentaries have been made at the property.

‘Rowhurst’ viewed from the east, with Fire & Iron Gallery just visible beyond it.

The top left-hand part of the house was built in 1632 on an older ‘semi-basement’, and the right-hand part was built in 1346.

Lucy has spent her professional career in the field of modern ironwork, but she is just as enthusiastic about her ancient home. Numerous exhibitions, lectures and open days have taken place to explain the house and its place in Leatherhead.

After researching its history for three decades - fleshing out the bones of what was thought to be a Jacobean hunting lodge - Lucy commissioned dendrochronology, which dated the timbers of half of the building to an earlier 1346, and half to 1632. This left the anomalous semi-basement, built from flint and older than the structures above it. Rowhurst’s unusual terraced garden fascinated Lucy, too, with views right across Leatherhead to the Mole Gap.

Having assembled archives of medieval documents, maps and incredible photographs from the 1890s onwards, Lucy realised she could go no further without archaeological investigation to explore her ideas. Her desk-based research revealed links between this immediate landscape and King Alfred, Piers Gaveston and Dick Whittington. Once there was King Alfred the Great’s Anglo-Saxon settlement and minster church, a pre-conquest manor house, a major rabbit warren, a prison, a courthouse, a dovecote and a gatehouse. Was Rowhurst’s semi-basement one of these, or none of these – or all of these?

Surrey Archaeological Society came to help in 2019, and found Late Bronze Age, Early Iron Age, Roman, Late Saxon and medieval pottery under the lawn. A possible post-hole was identified, with a sherd of chunky Roman amphora from Baetica in Spain at its base. The digs were run as community outreach events, with local families and schoolchildren learning about Surrey's past. The archaeologists plan to excavate more ground at Rowhurst over the next few years.

Surrey Archaeological Society working with visitors and Saxon re-enactors at the community outreach day at Rowhurst, May 2019.

Anyone coming to see the modern metalwork will glimpse the outside of Rowhurst. Open days enable closer inspection and participation. Everywhere, contemporary metal art sits comfortably with the old buildings, and there was one major surprise for Lucy last year. The archaeologists found foundry slag and iron ore across the whole site, and not from the Quinnell family’s 88 years of blacksmithing here. This is not the first time the site has hosted ironworking…

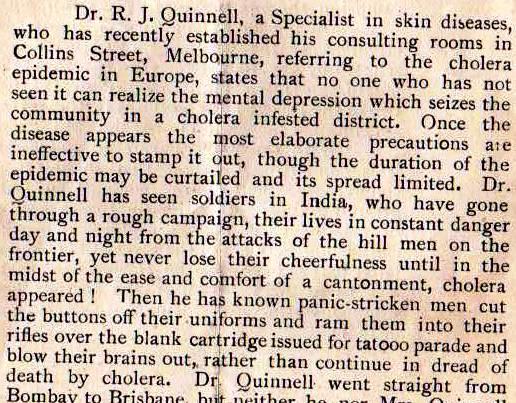

Lucy’s family first came to Rowhurst and founded a forge in 1932, and alongside her investigations into the site’s history she has done a great deal of geneaological research, revealing an interesting insight into the history of a craft from the 1500s and the social history of America, India and the UK from the 1700s. Aspects of this story are highlighted for special events, such as a display at Loseley House in 2010.

Fire and Iron's site is ecologically significant and is managed organically to protect its abundant wildlife. Woodpeckers, Great Crested newts and endangered flora are often seen by visitors. In 2016, Fire & Iron won the Surrey Wildlife Trust Gold Award for Wildlife Gardens and was the overall winner in the business grounds category.

In 2011, Lucy headed the campaign to 'Save Teazle Wood' - a 57 acre woodland (including an Ancient Woodland) that was marketed as land with development potential. The woodland was purchased in July 2012, and is managed as a Site of Nature Conservation Interest with gentle community access for therapy, conservation activity, education and social benefit. A charity was founded to manage the project – the Teazle Wood Trust. www.teazlewood.org.uk

Teazle Wood - sunlight hitting the ground for the first time in decades after a volunteer conservation day clearing dead scrub.

Lectures on the various aspects of Rowhurst, Fire and Iron, Teazle Wood and blacksmithing are given by Lucy Quinnell - on site to small groups and off site to WI, Rotary, Probus, U3A, specialist organisations, colleges, etc. Fees are donated to support the education and improved living conditions of children in India, Friends of Teazle Wood and The Jinny Quinnell Memorial Trust (palliative care and travel scholarships for blacksmiths).

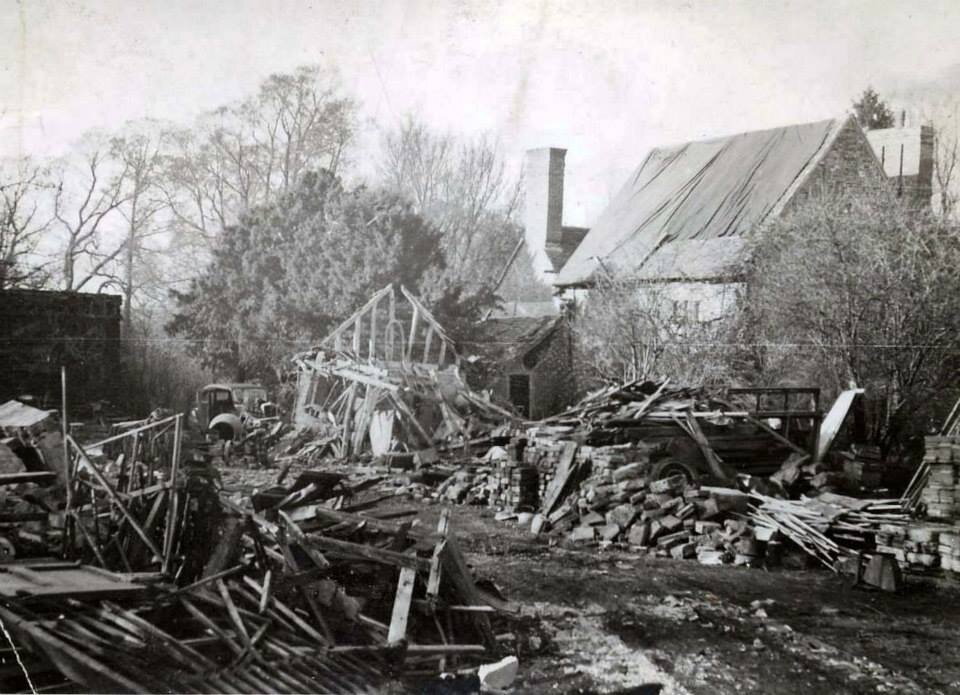

Simultaneously, Lucy is restoring the house. The house in its current form was in extremely poor condition in 1932 (and records describe its poor condition (“ruinous”, even) as early as the 1700s); it has been ‘patched up’ many times, but now requires a very careful and intelligent approach to what will be a long-term programme of restoration and conservation.

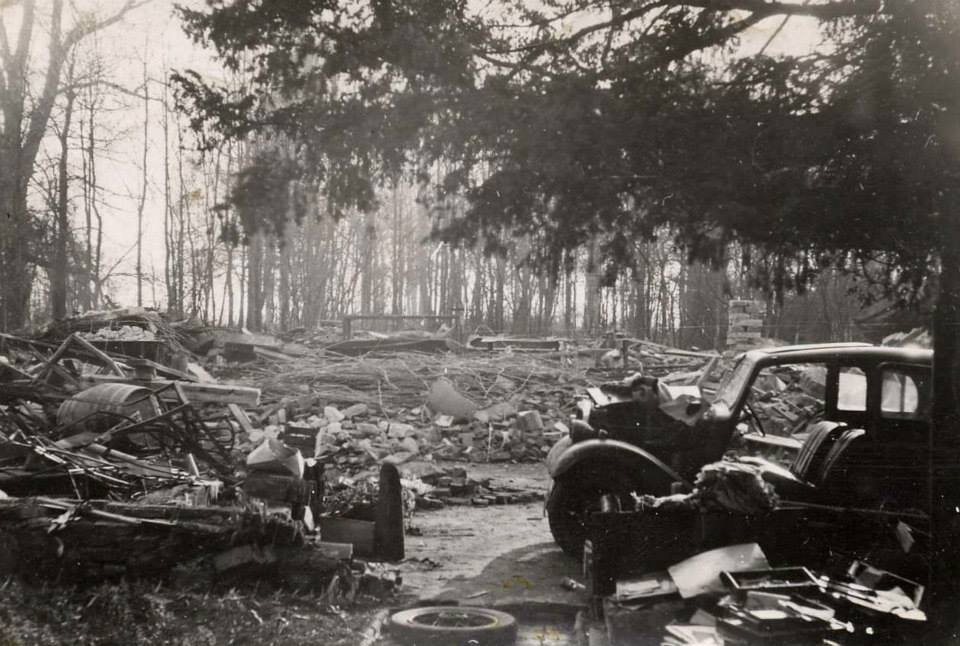

‘Rowhurst’ circa 1932

“In 2018 I engaged Dr Duncan Philips a highly-experienced listed building surveyor, to help me understand what should be done and in what order, and prior to this I needed to know what I was trying to restore Rowhurst as. This, in my opinion, depended on establishing a clearer picture of its history – for example, restoring the semi-basement as part of a family home is very different from restoring it as the remains of an Anglo-Saxon church that experts and the general public might be very interested to see on an ongoing basis; I needed to know what it has been in order to decide what its future is. Over the past few years, I have gained enough insights into its history to realise that it is of more than immediate interest to our family only, and that others enjoy and benefit from having occasional access to it. It is with this in mind that I am approaching the further investigation of and careful restoration/conservation of this precious building and its landscape.”

Many of Fire & Iron’s visitors have asked us to update them on this website re. Lucy’s progress in understanding the history of the site, and here below is her latest summary in note form from March 2020. **Surrey Archaeological Society is hoping to resume its forums and digs at the Rowhurst & Teazle Wood sites in Autumn 2020, Covid-19 circumstances permitting. We will post details on here.**

Revealing Rowhurst

How the land lies - by LQ March 2020

Summary of thoughts to date

I have been researching the history of my Grade II* Listed house ‘Rowhurst’ and the wider North Leatherhead landscape for 30 years now, and with the help of others I feel I am at last just within reach of some of the answers to the biggest questions about this enigmatic part of Leatherhead.

When I first moved here in 1990 I wanted to work out how Rowhurst fitted into Leatherhead, as it seemed so far north of the town centre and yet ‘Leatherhead’ was its postal address. (At Exeter University I studied a module of my English degree course entitled 'Land, Landscape and Literature' - I've always felt passionate about man's practical and romantic relationship with landscape, and very aware of local literary and landscape gems and connections that have gone largely unnoticed by the town. ‘The Mounts’, for example, is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, but few people know this. ‘Randalls Park House’, just across the road from The Mounts and demolished in the 1930s, is surely ‘Randalls’ in Jane Austen’s Emma, but again no-one knows this...). I was born in North Leatherhead (Kingston Road), grew up mainly in South Leatherhead (Clinton Road), and came ‘home’ to Oxshott Road in North Leatherhead thirty years ago.

From day one, Rowhurst seemed to me to sit very strangely in its location – built deep in the ground and low in its setting, despite being just a few metres down from the highest point in the area. It floods in wet weather, which seems absurd when we are so high up in the general location. An Iron Age coin - a British Q gold stater - had been found at Rowhurst in 1960. The local history accounts and Listed Building description suggested Rowhurst was built c. 1550 AD and had later been used as a hunting lodge for Hampton Court Palace. The grounds are substantially terraced, with a long flat platform dominating the garden, higher than the house and edged on its north side with very old hedgerow.

‘British Q’ gold stater found at Rowhurst in 1960.

As I got to know the house better, I found it more and more intriguing. I set out to prove its 'credentials' and could find no entries in Hampton Court Palace records to suggest a Royal hunting lodge (Simon Thurley helped me with this – he could find no mention of the word ‘Rowhurst’), and no real evidence of whether it was 1500s, 1600, 1700s... Science leapt forward, as it does, and I commissioned a dendrochronology survey. This came back with the dates of 1346 for the service wing (MUCH earlier than expected) and a 1632 date for the large brick addition. This still left our semi-basement, which is 25' square with 2.5' thick flint walls, and very deep foundations (sketch below, showing the semi-basement only), and I am certain it is older than the 1346 wing. Our local Domestic Buildings Research Group studied the building and described it as an example of ‘alternate re-building’, with a medieval hall, later service wing, and then the large brick house of the 1600s; they concluded that the hall and its footprint were now lost – but are we sure of this? Could the semi-basement be the older medieval building that the service wing was attached to?

The 1300s dendrochronology date obviously caused a stir, and it also triggered my interest in the older history of the wider landscape of Pachenesham/Pachesham Manor (North Leatherhead). Rowhurst is right in the centre of Pachenesham Manor geographically, and by this time I understood the history of modern Leatherhead as a later merging of the two separate medieval manors Pachenesham and Thorncroft. Modern Leatherhead is roughly like an hour glass, with Pachenesham Manor the north bulb and Thorncroft Manor the south bulb, as it were. The current town centre is at the neck of the hour glass, and developed in medieval times when a licence was granted to the people of Pachenesham to sell their wares to the people of Thorncroft there. Pachesham is on heavy London clay and dominated by marshland, blackthorn, oak and ash. Thorncroft is on chalk and characterised more by beech trees. Socio-economically, North Leatherhead has been recorded as one of Surrey’s most deprived communities, and South Leatherhead is regarded as wealthier.

I had already read about the missing Anglo-Saxon Royal vill and minster church of 'Leodridan' [Leatherhead] in King Alfred's will, and had not associated these with Rowhurst in any way, until Stewart Ainsworth of Time Team fame commented during one episode that "A ridge between two streams is the classic site for an important Anglo-Saxon building". I already knew that the lost Royal centre and church were associated with Pachesham and not Thorncroft. Rowhurst is on a ridge between two streams (Rye and Strode), with marsh around the base of the ridge, and the medieval Pachenesham settlement, the moated manor site of The Mounts (moated manor house built in the 1200s – there is no evidence of earlier buildings on its immediate site), and the River Mole on the flat flood plain all situated at the western end of the ridge. There is a spectacular view from Rowhurst to the south right through the Mole Gap between Box Hill and Ranmore (although this is now largely obscured by trees).

This was the first time that I asked myself whether our mysterious flint semi-basement and landscaped hilltop could have any possible connection with the rich Anglo-Saxon history (and mystery) of the immediate area.

Over three decades of gardening, burying loved pets, etc., I (and my family) had also started to find large chunks of building material that are not from the current Rowhurst building. Big pantiles, a substantial piece of carved Lower Wealden Greensand column, some chunks of 'egg and dart' pattern plaster frieze, a small chunk of Roman tegula, etc.

I wrote to many general addresses seeking help (such as Historic England), but never received any responses. The Domestic Buildings Research Group visited to offer insights, and Mike and Esmé Rubra took an interest, too, for which I remain very grateful.

In 2011 the badly neglected and rubbish-strewn (but ecologically rich) 57-acre woodland on the ridge (between Rowhurst and The Mounts) suddenly went on the market as 'land with development potential'. I am very interested in ecology and its indisputable value for biodiversity and for people, and I ran a local campaign to 'Save Teazle Wood'. Against all the odds, and thanks to incredible support from the community, in 2012 we were successful, and it is now run as a community nature reserve and charity (Teazle Wood Trust) with Heritage as one of the 4 charitable aims (Ecology, Community, Heritage, Education). The highest section of the wood is Ancient Woodland; on the lower slopes we have all inadvertently purchased the entire footprint of a Victorian brickyard, which is rather fantastic! This obviously extends my and others’ interest in the landscape and local social history, and it also extends the community's opportunity to properly investigate its own story.

Two or three years ago, one of the woodland and river volunteers - Nigel Bond, who is a member of Surrey Archaeological Society - began to take a much keener interest in my feelings about this land than anyone else had previously, along with a Woodland Trust heritage archive research volunteer Keith Lelliott. I had dug an amateur test pit in some desperation in 2018 - I felt that if after 30 years I could not get any serious interest in the site, Rowhurst (if indeed it did turn out to have more to offer than met the eye, as I believed) would be incredibly vulnerable when I'm no longer around, and I was keen to ‘provoke’ that interest before it's too late - much of the land has gone for the M25, and the rest is very rapidly disappearing under careless development. I immediately found a flint-surfaced slope and some Roman pottery. Nigel kindly offered to get SyAS involved, and in 2019 he and pottery expert Lyn Spencer organised two official SyAS community digs, with educational supervision from Community Archaeologist Dr. Anne Sassin. During these, they found quite a volume of Late Bronze Age, Early Iron Age, Roman, Late Saxon and post-Medieval pottery in Rowhurst's terraced garden, along with numerous burned flints and pieces of foundry slag, and a distinctive layer of charcoal, terracotta and chalk fragments across much of the site. A ditch was explored right on the top of the ridge close to the current Barbed Wire sculpture. During the second dig in October 2019 in a trench closer to the house on the slope of the lawn between the current pond and standing stone, the archaeologists found what appears to be a posthole with a thick sherd of Roman amphora at the bottom. Nigel Bond wrote re. the RTW19 October dig: “This has been a very successful dig despite the clay which meant that we were only able to work on one 5 x 1 metre trench, reduced to 5 x 0.5m for the second half of the dig. Our philosophy of saving everything resulted in much work for our patient team of finds processors. Key discoveries include many Prehistoric potsherds, some Roman and, for the first time at Rowhurst, Medieval pottery (S2 Shelly Ware pre 1050-1250 AD (Geoffrey's pot) and Q1 Sandy Ware 970-1100 AD). With Mark Eller's help we are now able to more confidently distinguish between natural undisturbed clay and redeposited clay. We found a linear or gently curving line of redeposited material running along our trench with a post-hole within it (at least I don't know what else it might be). The flint packing formed a U around the lost post which apparently sat on a thick amphora sherd which had been displaced along the axis of the U. So we have of our first evidence of a built structure in this part of the site.” I had also identified a seam of siderite close to the site, with the help of iron smelting expert Owen Bush, and more pieces of siderite were found in the test pits and trenches. One of the archaeologists suggested that we might eventually find that the shaped landscape was at one time an Iron Age hillfort. SyAS are due back for a symposium and more digging (now hoping to achieve a 5-year programme), but have been delayed this spring by the Covid-19 crisis.

Some of the Prehistoric pottery is of a type that has tended to be found on 'fortified, aggrandised' sites of high social status and authority - flat, flint-tempered, perforated clay plaque thought to have been used for baking flatbread.

Armed with all of this new information, I returned with fresh eyes and a new understanding to the work I had studied carefully in the 1990s by Ruby and Blair, and the Pachenesham manorial rolls, etc.

The word Rowhurst (Anglo-Saxon, meaning 'rough wooded hillside' or similar) first appears in records of the early 1400s, as a 'field' owned by Simon Wrenne - but bear in mind that the timber-framed service wing of the house itself dates from 1346 so must have existed already and is perhaps listed nearby under a different name or description, or was ruined? It first appears definitely as a house when it is left in Robert Marsh's will of 1684 and then surrendered by Robert Marsh (same man, or a relative) to Robert Ragge in 1712 with 40 acres of land (in lieu of payment of a very substantial debt – Ragge was a local money-lender). It was still being listed with 40 acres of land as late as 1842. 40 acres rings a bell! The ‘church of Leret’ [Leret is widely accepted as Leatherhead] with 40 acres, worth 20s and held by Ewell Manor, features in Domesday Book in 1086, held by Osbern de Ow. This has led to speculation that the ‘church’ was an old minster associated with the Royal vill of ‘Leodridan’ [also accepted as Leatherhead – precise location unknown but associated with the Pachenesham portion of modern Leatherhead] in King Alfred the Great’s will (already mentioned above). In brief, the theory is that there should be an undiscovered Royal settlement and minster church still to be found by archaeologists somewhere in the Pachenesham area north of the Rye Brook. (Nigel Bond has done some very interesting work trying to trace the ‘40 acres’ through time, concluding that Rowhurst’s land and Teazle Wood close by are at least viable candidates).

Interestingly, the word 'Slaghurst' also appears a few times in the manorial roles, often in association with The Mounts. It means much the same as Rowhurst (‘rough wooded hillside’), but perhaps with more of a potential connection to ironworking? Are they one and the same?

I have tried to work forwards - and also backwards, as I have a pretty full history from 1712 to the present day.

In 1544, Rowhurst was surrendered to the Crown by Nicholas Legh in exchange for lands at Addington. I'm doing some fact-checking to try and grasp the 1500s/1600s, and it is more interesting than I anticipated; so much political intrigue and favours for mates... Again, perhaps I hadn't grasped the impact of all the Crown/state/church carryings-on on this little Leatherhead plot in the middle of nowhere.

Nicholas Leigh/Legh was the son of John Legh of Addington and one of the Leghs who had built up substantial holdings from the Wyghts and Bakers in Headley, Ashtead, Leatherhead, etc., (it was handwritten as 'John' in information kindly sent to me years ago by Derek Renn for L&DLHS, but I’m now sure this isn't correct, and it looks like it was 1544 not 1543 as Derek said – but this must be double-checked again [07/02/21 - both John and Nicholas are correct, and both 1543 and 1544 - see https://docplayer.net/190882227-I-f-lg-issn-proceedings-of-the-leatherhead-district-local-history-society-vol-4-no-8.html ]). Nicholas Leigh was an MP (for Bletchingley), so we are very much looking at a period of 'property shuffling' for Rowhurst as I said in an earlier email - Parliament/Crown/church/private. If I can nail how and when it then went back from Crown ownership in 1544 to private it will really help (it could of course turn out to be the property given to Edmund Downing MP and John Walker and their heirs in 1579 ('excommunication of Elizabeth I by the Pope' era) – see below, which is a neat transition back to private ownership in time for Robert Marsh later on in the 1600s). Cronyism springs to mind at every turn in this story! I still think that the owner of nearby Horton Manor, with his connections to Sir Basil Brooke in Shropshire, George Mynne MP will feature at some point.

In 1632, someone who wasn't flush with cash (Martin Higgins' words!) put the big brick house on top of/beside the rest - rather bodged and done in a hurry, but for someone of status or wanting to impress someone of status. My best guess is George Mynne, Robert Marsh or Downing’s heir Robert Morley, but this stage in Rowhurst’s story is tantalisingly missing from any records.

Rowhurst has always seemed to fall outside the main records, and that seems to me to add weight that it might just be a candidate for the Ewell Manor / Merton Priory 'oddment' enclave that contained the minster. The Ewell Manor land went to Merton Priory, so presumably the rental paid to Ewell Manor went with it and was thereafter paid to Merton? I thought that if I traced it 'forwards' on this occasion I should be able to see what happened to it. Looking for Pachenesham records very recently, I discovered an entry under 'Pakenham' which phonetically piqued my interest (locally, we now say Patchesham, but occasionally people still call it Packesham). I then saw that it said Pakenham at Leatherhead, and importantly it added "Nothing further is known of this manor", whereas of course it is still here: "The priory of Merton had an estate in Letherhead which in the 16th century is called the manor of PAKENHAM. In 1535 the possessions of the monastery in Pachevesham were valued at 20s. In 1579 'the lordship and manor of Pakenham in Letherhead, late part of the possessions of the monastery of Merton, was granted to Edmund Downing and John Walker and their heirs. There seems to be no further trace of this manor." The record related to documents at Merton College Library, so I contacted the Library (see below) and Julian Reid there was very helpful. He says: "I have checked our catalogue. These are certainly our references but I note that our catalogue refers to the manor of Thorncroft, Leatherhead, but not to the manor of Pakenham. In contrast, the Manorial Documents Register distinguishes between records of the two separate manors of Thorncroft and Pakenham. In mitigation, our manorial records were catalogued in the late nineteenth century and there has been no modern re-cataloguing. It is possible that the existence of records in our archives relating to the two separate manors may have come to light during the ‘recent’ revision of the MDR."

These might be records pertaining to Pachenesham that no modern historians have seen, although Professor John Blair who did so much research into the area feels sure he would not have missed anything – but he didn’t know about the Downing/Walker record, so have I stumbled across something new? The 20s value is the same as the value given in 1086 and later evidence had already suggested that this value had become ‘fossilised’; can I safely conclude that the ‘church of Leret’ worth 20s and held by Osbern de Ow and owned by Ewell Manor is the same property granted to Edmund Downing and John Walker and their heirs? We know for certain that Ewell Manor was granted to Merton Priory 1121 and owned by Merton Priory until 1538 and the Dissolution of the Monasteries; the Pachenesham plot containing the ‘church of Leret’ in 1086 would have been part of the Merton Priory possessions - whether ruined or vanished by the 16th century – and if we can establish what Downing and Walker subsequently did with the Leatherhead property granted to them in 1579 we should be able to firmly identify the glebe of the missing church. Rowhurst was certainly being shuffled around between Crown and private ownership in that period, but there are of course other candidate sites (including Teazle Wood) and it would be good to know for sure.

(I've since been doing research into Edmund Downing and John Walker, and a theme is well-and-truly emerging! Puritans, Parliament, Suffolk and Cambridge Colleges, particularly Emmanuel and Downing, and Harvard...

The 'Pakenham in Leatherhead' land granted to Downing and Walker and their heirs in 1579, formerly of Merton Priory (formerly of Ewell Manor), is almost without any doubt the enclave of land associated with the missing church of Leret of 1086. It's described as having been valued at 20s in 1535 and having formerly been monastic land belonging to Merton Priory.

Rowhurst and nearby land might well be this land (fingers crossed), or it might be a chunk of land somewhere else in North Leatherhead. But it is in Pachesham somewhere.

In brief, so far I am seeing a picture of Puritanism on a grand scale and a real 'web'. [Because of trying to prove or disprove the James hunting lodge connection for so long, and feeling through both the Hampton Court records and the dendro date pushing the main house into the reign of Charles I that we were dealing with Royalists like George Mynne round the corner, that has been my focus - looking from the other direction (the Puritans and Parliamentarians, and with the new possible Downing/Walker connection), things look very different indeed].

I am only skimming through info at the moment, but can see a real story emerging:

Edmund Downing MP, associated with Sir Walter Mildmay and Sir Francis Walsingham and from a wealthy Suffolk Puritan family, had two daughters, so his HEIRS were (by marriage to the daughters) Sir Edward Alford MP and Herbert Morley MP. All are big Puritan players and Herbert's father was received into the congregation of leader of the Reformation John Knox at Geneva in 1557. Herbert Morley and Dorothy Downing had no children, so Herbert left his state to his half-brother Robert Morley MP. Edmund Downing was the MP for Higham Ferrers from 1572, an estate with a large rabbit warren and fishpond, associated with Mildmay.

I cannot trace a John Walker other than John Walker Archdeacon of Essex, staunch Puritan and voter for Reformation, with strong Ipswich and other Suffolk connections and studied at Cambridge University. He was almost exaclty the same age as Edmund Downing (his BA at Cambridge is down as 1547-8, so his birth date is estimated at very late 1520s - Downing was born in 1530). Walker died in 1588, so could plausibly have been 'our' John Walker in 1579. The newly discovered Oxford documents should show this when we get to see them. Link below to info about John Walker Archdeacon.

If we assume that John Walker had no heirs (he died without issue, although he may have had a will), let's look at the Downing heirs Edward Alford and Herbert Morley. Edward's father sat in the House of Commons and was Secretary to Sir William Cecil Lord Burghley (who had of course very close links to Elizabeth I and Sir Francis Walsingham). Edward died in 1632, and his heirs were his children William Alford and Elizabeth Alford. Herbert and Dorothy had no children, and Herbert died in 1610 leaving his estate to his half-brother Robert Morley. Robert died in 1632 as well (it may prove relevant that Morley was a member of the Worshipful Company of Skinners). 1632 is the year Rowhurst’s major brick addition was built, and the initials RM are carved into the chimney stack.

Edmund Downing played a key role in helping Sir Walter Mildmay to found Emmanuel College, Cambridge (where I was interviewed in 1983 but didn't get in!). Edmund Downing's nephew Emmanuel Downing married Lucy Winthrop, sister of John Winthrop (English Puritan lawyer and co-founder and Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Winthrop . Lucy is quietly credited with being the real founder of Harvard! She had married Emmanuel Downing and had a son George - her brother John wanted them to join him in America, and Emmanuel Downing represented the Massachusetts Bay Colony before the Privy Council in London on behalf of the colony. Lucy was a Puritan and worried about the questionable behaviour of Cambridge students influencing her son George, so she seems to have done a deal with her brother John - she and her family would go to America IF a college was founded for her son George to attend (and Harvard was born - look at Harvard University's address - Cambridge, Massachusetts; the whole family was into the idea of founding Cambridge colleges: Emmanuel College, Harvard at Cambridge Massachusetts, and further down the line, Downing College, Cambridge, founded by Lucy's great-grandson George Downing). Lucy and Emmanuel's son George was then indeed in the first graduating 9-student class at Harvard. He went on to become Sir George Downing 1st Baronet, supported Cromwell and supported the execution of Charles I but also worked for Charles II. He married Frances Howard in 1654 (she was the g-g-daughter of the 4th Duke of Norfolk - the very powerful Howard family) who was a cousin of Charles Howard, 2nd Earl of Nottingham of Effingham, Surrey (known until 1624 as Lord Howard of Effingham) - he had died in 1642 in Leatherhead when Frances was about 20. The marriage aided George Downing's advancement and he is known as a nasty, self-serving, disloyal piece of work and "a preacher, soldier, statesman, diplomat and spymaster and politician whose allegiances notably changed during his career". Downing Street is named after him - he owned the land there. He was scoutmaster-general of Cromwell's forces in Scotland. One of his nephews is thought to be (but not absolutely proven) Colonel Adam Downing who fought for William of Orange in the Siege of Londonderry and the Battle of the Boyne and is the 'gallant Adam Downing' of the famous folksong.)

I have also deduced that the main road from Guildford to Kingston originally crossed the Mole close to Fetcham Splash and on across the fields and later along what is now Oaklawn Road, which makes absolute sense. Local history interpretations conclude that Bygnallane went from Guildford through Bookham and through what is now Leatherhead town centre and out along Kingston Road, L'head, toward Chessington and Kingston, but it's not that long ago that the route I prefer was still called Bickney Lane. This would fit with the theory that Pachenesham is indeed the lost Royal centre.

It is also noteworthy that Rowhurst had a very substantial barn next to it until 1871. It is shown with two entrances on the 1842 Tithe map, like the big Grange/Tithe barns. Its age is unknown, or whether there had been earlier versions on the same plot before it.

And, it is also worth mentioning the 'Roman building' that features on Mole Valley District Council's maps for the area. This is the square feature with strikingly familiar 'flint, chalk, tile' finds and the Romano-Celtic enamelled roundel find looked at by Lowther, and was close to Dorincourt in the 'Woodlands Park' grounds at the time. It is just 500 metres across the Strode valley from my house - I could wave to someone standing there. Square flint buildings on clay and two in the same vicinity - is Rowhurst's semi-basement one of a pair?!

I also had a stroke of luck recently whilst running a Teazle Wood conservation task day in the woodland in January 2020, less than 300 metres for the moated manor site of The Mounts:

We were clearing blackthorn scrub away from a couple of very distinctive features that showed up on LiDAR maps. I set our stalwart volunteers the challenge of deciding what these features are (I didn't know the answer). They are not bomb craters and they are removed from the activity of the Victorian brickyard. One is like a giant ring doughnut sitting on the ground (40'-50' diameter, and about 4-5' high) and the other comprises two parallel mounds. The round one fills with water in wet seasons, but appears to have originally had big drainage channels to let the water out, that have become blocked with leaf matter, soil and brash. During the conversations (i.e. Pugmill? No, there is one already located, well-documented, and very different, and this current feature is too far from the clay pits; etc.) I said I thought it might be a rabbit warren, because I had read somewhere in medieval lists that someone in Pachenesham had "built a warren there". This was a fairly casual theory, but later that day I looked up the record again. It related to Sir Eustace de Hache, and was dated 1292. Nine years earlier, de Hache had superintended the building of Caernarfon Castle (and Beaumaris and Conwy) for Edward I (which may explain why Piers Gaveston is then associated with Pachenesham as the next Lord of the Manor?). de Hache was not an absentee - his son's baptism pageant processed through Leatherhead and was held at Thorncroft because de Hache had allowed the Pachenesham chapel (St. Margaret's) to fall into disrepair. This made me research medieval rabbit warrens a little more carefully, and I immediately realised that they were not the small-scale domestic set-up I had in my ignorance assumed them to be. Of course! In very brief medieval entries, if they said "He built a rabbit warren there" it must have been a very substantial one to warrant a mention. Am I right in supposing that the man involved with three major Welsh castles would not have done things by halves? Having now seen the scale of high-status medieval rabbit warrens, I appreciate the significance of that record much more than I did before. As I Googled, I saw Thetford Warren Lodge, and it leapt out at me. It is so like Rowhurst. This fits, and hasn't stopped fitting as I investigate further. Some warreners’ lodges were built into the ground, as the downstairs was the 'rabbit factory', so needed to be mighty with small windows for defence, and cool for storage. This would neatly explain why Rowhurst is so buried into the clay, with rusted out iron bars at tiny windows, and with so many alcoves/aumbries/cupboard niches. The family accommodation was an 'upper ground floor', which again fits the strange levels at Rowhurst. Lodges often doubled as upmarket hunting lodges, and as at Theford, they were extended over time as hunting became an increasingly fashionable leisure pastime. This would explain the later history and style of Rowhurst as a presumed hunting lodge (and it was still lived in by a gamekeeper in the late 1800s – Henry Rogers). They sometimes used old Iron Age hillforts, because some of the earth banking required was already there, and the warren was usually north-facing, which is the case with all the distinct terracing at Rowhurst. They were often very substantial, and had a tower as a symbol of status and for security - again, Rowhurst's chunky flint walls and deep foundations suggest something pretty major went on top. Some have a burned layer close to current ground level, where vegetation was burned before building the warren - could this explain Rowhurst's entire landscape having a layer about 8" down of little flecks of charcoal? Thetford Lodge is described as 'just off the top of the warren' - Rowhurst sits ‘just off the top’ of the ridge.

I do feel it is the first theory that really fits as a reasonably plausible one, and also doesn't discount the possibility of the intriguing wall that is ahead of you as you enter the semi-basement being older still (the probable Roman posthole suggesting structure, and then Saxon pottery close to that, does suggest a history of some kind of building set-up on the same plot going back a long way, rather than someone just popping a brand new warren lodge in a fresh field). The unusual floor levels, the fact that the walls are so thick, the deep foundations, the tower-like nature of the shape, the rusted out iron bars at very small windows, the strange mix of humble/posh, the assumption/rumour that it was a hunting lodge, the later development of it, the contoured grounds, the written entry for a warren, the association with an ambitious and experienced builder in de Hache. The wider territory is undeniably good for gamekeeping/hunting, as we have so much evidence of people using it for that right up to the 1800s with gamekeeper Henry Rogers. The Surrey Union Hunt favoured Leatherhead Common, and of course Prince Leopold of Belgium’s/Prince's Coverts are immediately north. I'd missed this so spectacularly just because I had a preconceived notion both of hunting lodges and rabbit warrens - it hadn't occurred to me that the two things could meet in the middle! The cultural notion of rabbits for me (I love them!) had more humble and low-status associations with Fetcham pet shop and tiny hutches..!

When I moved here in 1990 I had pet rabbits, and there were literally hundreds of wild rabbits and it was almost overwhelming - never any need to mow the lawn. The M25 was fairly recent at that time, so that giant chunk of landscape had gone, and they were much more landlocked, along with their predators. When the landowner nextdoor scraped his 7-acre land they just dwindled away and now we just see a very few - I guess they'd had so much edge habitat that they don't have now, and the foxes and buzzards, etc., are more desperate for food because of habitat loss, and of course disease plays a part. BUT, I can vouch for the fact that rabbits can thrive on this landscape. There seem to be many more still on the land on the other side of the M25.

This is just a taste of the vast amount of information, archaeology, building materials, maps, photos, etc. I have now amassed. I have to work out a way of progressing and recording it all.

My gut feeling (involving some leaps of faith) as to the most plausible summary of the history is now as follows:

There has been human occupation of this hilltop since at least the Bronze Age. It is defendable, and well-placed between other key places. Something else may have attracted people - it's London Clay, and there seem to be ferruginous ‘chalybeate springs’ or at least iron-rich standing water/vernal ponds, and we are just investigating this with the help of Surrey Archaeological Society and their geologist. Ashtead Roman Villa and the Iron Age earthwork close to that are just 2.5km to the north-east, and on the same soil and raised landscape that ends in our ridge, and Ashtead Local Ware was found by me in 2018 and by SAS in my garden in 2019.

Perhaps there was a sacred element to the ferruginous water (we found 3 x Roman curses, and there are 7 wells and ponds immediately around/tight to Rowhurst; a Lord Rothschild who grew orchids used to come to the Teazle Wood brickyard to buy flowerpots for his orchids, because the clay was famous for being mineral-rich). Might this have made it an attractive location for a later Anglo-Saxon settlement/church? Could it be the natural defendable location for the vill and the pre-conquest manor site? Is the giant barn (or possible predecessors on its footprint) relevant, if the Royal vill served as an economic centre collecting tithes, as suggested by historians?

In the 1200s Brian de Therfeld and later Eustace de Hache developed the moated site further down on the flood plain. The excavation of that site describes stone as a building material - could the large chunks of greensand stone found scattered at Rowhurst be the remains of a building that was 'robbed' c. 1203 to build the manor house at the Mounts just downhill? Or, when Eustace de Hache made the improvements to Brian de Therfeld’s first version of The Mounts, did he add the stonework and did he build a matching warren lodge with similar stone just up the hill? (And later on, both were robbed of the stone). It’s worth noting that Rowhurst’s semi-basement flint walls are the same thickness (2’6”) as those excavated at The Mounts.

Did de Hache use the wider site as a major rabbit warren, transforming any earlier ruins or just building the Rowhurst semi-basement afresh on an ancient banked site as a warren lodge and major tower-like status symbol? Is there a connection with the 'gatehouse, prison and pound for beasts' in the records? Rowhurst is on the promontory overlooking The Mounts and the medieval Pachenesham village settlement - in several eras, they would not have occupied the low ground and left the ridge above them exposed and empty. 'Wydegate' gets mentioned a lot - were there impressive 'twin towers' in any era overlooking Bygnallane/Bickney Lane/Oaklawn Road, which still runs between Rowhurst and the 'Roman building'?

We know there was a chapel/church already in disrepair when de Haache was in residence - could that be the missing Anglo-Saxon church? It should be on a nearby high point, which Rowhurst is. There is also a high point in the Ancient Woodland part of current Teazle Wood – my favourite church location candidate.

If we assume that Rowhurst's semi-basement might be a rabbit warrener's lodge in 1292, that is perfect timing for the fine addition of the 1346 high status service wing as a typical improvement for upmarket hunting guests (just a few months before Crecy). I speculate that this was then empty for a while (the Black Death was disastrous for Pachenesham); William Wymbledon stole some of the roof timber in 1383, leaving the inside badly weathered in situ (dendro evidence – “weathered in situ, without its roof, for at least a century at some point in its history”) and in 1481 someone did it all up again and put a new roof on it (dendro evidence, carved roof timber). In 1535 it is valued if it is the ‘20s and 40 acres’ plot, and in 1543/1544 John & Nicholas Leigh surrender it to the Crown in exchange for lands at Addington. The Crown gives it to Downing (Compteller of the Exchequer) and Walker in the later 1579. They must sell it or bequeath it to someone, and in 1632 Robert Marsh (possibly - the initials RM are on the chimney stack; or heir of Downing Robert Morley who died in the same year – 1632) cobbles together at speed an impressive-looking hunting lodge for reasons unknown (but in an era of impressing people, hiding people, meeting people). He or one of his sons, also Robert Marsh, leaves his house Rowhurst in his will dated 21 October 1684 and then, in huge debt to local money-lender Robert Ragge, the same or another descendant Robert Marsh surrenders it in lieu of payment of that debt in 1712. The rest we know with much more certainty! The history from 1712 is detailed and interesting, especially when combined with that of Teazle Wood’s brickyard.

SyAS will be digging again, Covid-19 events permitting, in the autumn, and 'following the Saxon pot'. In the meantime, I have a golden and rare opportunity to do some desk-based research.

I have also been comparing the topography to Tuesley Manor site, where Godalming minster is thought to be. Same history as the Leodridan and Leret entry, and it is - like Rowhurst - a ridge between two streams with an M-shaped approach road. We have Ashtead next to us; they have Ashstead Lane - a smaller settlement producing ash wood for the main settlement on the ridge nearby? An ongoing wood supply would have been needed from somewhere close by.

And I’m now looking at Grade I listed Slyfield, to the west of Rowhurst and re-built as a grand house in 1610; its brickwork and windows share some similarity with Rowhurst and its large barn with double entrances is possibly similar to the double-entrance barn shown on the 1842 Tithe Map at Rowhurst but gone by 1871. The main road from Slyfield to Kingston and London would have passed between Rowhurst and the ‘Roman building’ close to Tyrwhitt House on Oaklawn Road (formerly possibly part of Bickney Lane) – is there any 17th century connection?

Lots to explore.

- Lucy Quinnell 30.3.2020

Earlier notes worth keeping, when LQ was assessing the square semi-basement (this was BEFORE her rabbit warrener’s lodge theory and Nigel Bond’s subsequent exploration of this rabbit warren theory):

“Anglo-Saxon church”? At the moment, I have no idea whether Rowhurst has any firm connection to Leatherhead’s missing minster church which is in King Alfred’s will (c. AD 885), and which is thought to be ‘lost’ in the Pachesham area of modern Leatherhead, where Rowhurst is centrally located in the original Pachesham manor demesne. However, archaeological finds, the atypical architecture of the flint semi-basement, the evidence in historical records and the geographical position of Rowhurst on a high ridge between two streams, combine to make it a plausible candidate.

I set out in March this year to more actively prove or disprove the church theory. With expert and amateur input, we now reach November with a greater collection of theories than we started with. The purpose of this document is to start to list the theories – however ‘wild’ or basic some might seem – and present in very simple form the evidence for each one, in order that we have something assembled and concise to show to new experts with interest in relevant fields, and so that we can pursue further or discard each or all of them.

My instinct is that Rowhurst is not straightforward, and that the current ‘house’, now dated in its two main builds to 1346 and 1632, is obscuring a much older story. Whether that story includes any or all of the elements that have been discussed this year remains to be seen, but I am determined to investigate this as far as I can while the property is in my care.

The current suggestions for an earlier history of Rowhurst, based largely on inspection of the semi-basement when combined with local evidence, include:

Roman temple

Cult room

Roman funerary tower/mausoleum

Roman bath house

Anglo-Saxon church

Anglo-Saxon royal vill

Court house

Burh

Saxon/Norman tower

Medieval hall

Medieval dovecote

Carolean undercroft

A combination of two or more of the above at different times

(The history from 1712 is fairly clear)

I will now expand on each of these.

Roman Temple

This was proposed because the semi-basement is strikingly square (20’ x 20’ internally, c. 25’ x 25’ externally), and we were debating with Heritage Open Days visitors buildings in history which have tended to be square in shape.

A Roman temple was suggested (or at least that the current semi-basement was built on the foundation of a Roman temple).

People did settle in the immediate vicinity in Roman times. A pre-Roman coin was found in Rowhurst’s garden in 1960 – a gold British Q blank on one side and with a stylised horse and chariot design on the other (Southern/Atrebatic).

A ‘Roman Building’ is shown on a MVDC map, approximately 740m west-northwest of Rowhurst . A Celtic bronze roundel was found here; this is of the type found elsewhere on Romano-Celtic temple sites. See following link for more details:

http://pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=397205#aRt

Roman pottery was found in a test pit in Rowhurst’s garden.

A Roman key was found just inside adjacent Teazle Wood in 2016.

3 small folded lead pieces were found along the top of the ridge from Rowhurst (into Teazle Wood) in 2013, and these appear to be Roman curse tablets.

Several large, thick terracotta tiles and narrow bricks have been found under and around Rowhurst to date. These are not from the existing standing building. Date of these tiles and bricks to be confirmed.

Roman tiles were found close to ‘The Mounts’ medieval moated manor site (Scheduled Monument), approx. 700m south-west of Rowhurst.

Ashtead Roman Villa is approx. 2.5km north-east of Rowhurst.

Cult Room

Strong similarities have been noticed between Rowhurst’s semi-basement and Lullingstone Roman Villa’s cult room / house-church (see below – courtesy ofHistoric England; illustration by Peter Dunn/Richard Lea)

It may also be relevant that Rowhurst’s semi-basement is built into a slope, with a building platform higher up beyond it on the top of the ridge. Lullingstone was built into a slope, with a temple-mausoleum higher up beyond it (later incorporated into a chapel).

**We do not yet know whether Rowhurst’s semi-basement was always half underground, or whether it was above ground and the ground level built up around it (more so on the south-eastern side) over many centuries**

Roman Funerary Tower/Mausoleum

This has been suggested because of the size and depth of the flint foundations of the semi-basement. These are very substantial (flint does not occur on the London Clay site, so it has been imported) and two eye witness accounts (the late Don Davy, and Richard Quinnell) report that when the outside steps were created for the semi-basement in the 1960s, the flint foundation went ‘out and out and down and down’. RQ states that the foundation went down a further 2 metres from the current bottom of the semi-basement steps and the bottom had not been reached, and Don Davy’s report to us a few years ago backs this up – he said that they went down 15’ from current ground level and still didn’t find the bottom of the splaying flint foundation. This is a mighty foundation, and perhaps suggests that whoever built it was planning to put something major on top of it – hence the various ‘tower’ theories.

Did the Romans even have funerary towers in England?

The five ‘niches’ and the arches inside the semi-basement are striking, and correspond in some ways to mausoleum niches. The large flint niche in the north-eastern wall is certainly ‘body-sized’ (see attached niche details).

Roman Bath House

This was suggested again because of the squareness of the semi-basement.

Three observations may be relevant here:

1. The ‘plumbing’ of Rowhurst’s site is interesting, with three wells and a damp patch in the current car park which may relate to spring activity. The semi-basement fills with water if the pump fails.

2. Rowhurst had a semi-circular patio extending from the house when I moved in – this shows in old photographs and was definitely in place before 1932. Whilst I strongly suspect it was simply the work of a keen ornamental gardener in the early 1900s, it is something of an oddment for a rural house, and just may have been inspired by an existing anomaly in the landscape. Roman bath houses often had a semi-circular room at one end.

3. We found a very odd complex of tightly-built terracotta remains 20 metres south-east of the eastern corner of Rowhurst, up the slope. This reminds us of the layout of Angmering’s Highdown Roman Bath House, with its ‘east sump’ – what was a Roman sump like, and is there any possibility at all that this terracotta structure could have been associated with a bath house? (See illustration showing Highdown Roman Bath House)

Anglo-Saxon Church

Many expert and amateur historians and archaeologists have concluded that the minster church listed in King Alfred’s will lies lost in the northernmost part of Leatherhead, which was once the ancient manor of Pachesham.

The church was associated with a royal vill, so we can assume that there would have been a complex of buildings – church, manor house, courthouse, buildings to accommodate collected tithes, etc.

By Domesday, the church land was attached to Ewell manor, and held by Osbern de Ow. Godalming minster had the same history as Leatherhead minster – it was, like Leatherhead, one of the five listed in King Alfred’s will; it then disappeared, and its foundation has now been located and it measures 6m x 12m. A description on the website www.ladywellretreat.org.uk reads:

“We know that there was an Anglo-Saxon settlement in Godalming in the late 6th and early 7th century. Because of the Anglo-Saxon belief that evil spirits or even human enemies would not cross water, the settlement was situated at the bottom of the present Holloway Hill. The ground was raised here and was bordered by the Rivers Wey and Ock. The rise of land behind Holloway Hill afforded perfect protection and the broad sweep of land in front down to the river gave good pasture and grazing land. Woodland surrounded the settlement and it was in that woodland that the Anglo-Saxons built their shrine to the God of War – Tew or Tiw, hence we have the name Tuesley in use today.”

The general geographical location of Godalming minster is striking similar to Rowhurst’s geographical location (see the LiDAR map provided by volunteer Keith Lelliott, and my sketch), and perhaps resembling even more closely the ‘Roman Building’ site near to us in Oaklawn Road.

‘The Mounts’ – the site of a medieval moated manor – is not the original manor house site for Pachesham, but rather was active from the 1200s-1400s.

So where are the original manor house, church and associated buildings?

Could Rowhurst and its site be the original lost royal, religious and legal centre of Pachesham? If not, what other candidates are there?

Rowhurst is located very centrally in the demesne of Pachesham Manor – were manor houses usually central to their corresponding land, or did they tend to be at the edges, or is there no pattern?

In 2015-2016, volunteer Nigel Bond did a great deal of research into the history of the Pachesham land, and especially the 40 acres associated with the church. He concluded that Rowhurst and land in Teazle Wood were viable candidates for the 40 acres, and therefore possible candidates for the minster church site.

As late as 1842, the Tithe Map shows a very large barn to the west of Rowhurst house, and another narrow tall barn at 90 degrees to the northern end of the main barn, forming an ‘L’ with the main barn. This no longer exists. The plan diagram on the Tithe Map shows what appear to be two large entrances to the main barn. This substantial building with its two entrances looks very like a tithe barn/monastic grange barn, but at this stage its age is unknown. I would imagine that an Anglo-Saxon tithe barn would not have survived until 1842, but perhaps the 1842 barn might have been a successor to an earlier barn or barns on the same footprint?

Rowhurst’s garden features a very large man-made building platform, up the slope from the house and right on the top of the ridge. We have found a packed chalk ‘corner’ here (whilst burying the cat!).

It is worth noting here that all over the Rowhurst site, at a depth of a few inches, there is a very obvious layer of chalk and terracotta fragments with burned black fragments (charcoal, I think, but it is slightly ‘glassy’). These are very obvious and evenly spread, and the black is not a film/layer, but individual scattered pieces. The chalk and terracotta pieces are clean and not charred at all.

Some of the very large tiles have been found in or very close to this part of the garden.

Older maps show a very large pond (bigger than the house footprint) close to the north-eastern wall (approx. 17 metres from the house).

I also noticed a very striking M-shaped road to and away from Rowhurst on John Rocque’s map of Surrey (1762). This is still discernible ‘on the ground’. What does this suggest? The Common Land starts immediately beyond this ‘M’ – might it be defensive, or to ‘funnel’ people, produce and animals into a centre for collecting tithes? Or is it a later feature? (See Rocque map – attached).

** A plain Byzantine altar cross has ‘always’ been in my house, used as a door stop, etc. No-one in my family knows where it came from. It may have come back with my grandfather from the Middle East in World War II. It is just possible that it was found on site, so worth mentioning. It looks very old but appears to me to be brass rather than bronze, and I know the history of brass is complicated.**

Rowhurst’s semi-basement could be read as ‘church-like’ – the arches are at a strange height in the wall, and I wonder whether they are windows of the type seen in many early churches – the internal height of one of the arches is 54” – probably just too short to have been a doorway, but similar in size, again, to the arched window recesses in many early churches I have looked at. I have sketched the flint and brick south-east facing wall of the house as if we were to ‘remove’ the brick house above it:

Aumbries: In the semi-basement walls there are four ‘niches’ and a large alcove. The niches to me look very like ecclesiastical aumbries. The large alcove is 7’ wide. See attached PDF for niche & alcove sizes and images, but here are two examples:

Anglo-Saxon royal vill

If Rowhurst’s semi-basement is not the remains of the Anglo-Saxon church, could it be the remains of one of the associated buildings – the manor house, for example?

Court house

As above, could the semi-basement be the remains of the buildings associated with justice that were part of the royal settlement?

Jurors in 1259 stated that the county court bench had until recently ‘always’ been held at Leatherhead (it had moved to Guildford and later Kingston).

Even if the semi-basement was not originally a building associated with justice, could its survival be due to court activity in the Pachesham area?

John Paddon offered the following theory:

“The survival of your building probably lies in its secondary use as a court house, the cupboard type cavities [see aumbry notes above, too - LQ] in the random flint mortar walls are supportive of this interpretation, and the large platforms could be relics of taxation barns and possible home of redundant building material…

I think the layout of your challenge is the court house, as it has the massive flint in mortar walls with their cupboard cavities, which do not penetrate the thickness of the wall, which is not thick enough for a single span vault, so the possibility that it was capped by a timber floor, the beam slots having been eroded and/or also their position was above the current ceiling/floor. The Minster would have contributed the high level dressed flint work to the house, Saxon windows could easily have placed above the surviving levels, I recall seeing the Saxon, west end window, in the Godalming parish church which is nearly above the level of the tops of the inserted late gothic windows. The next Church west is Compton, Saxon with a 2story chancel and quite large. Further north and west and into Hampshireis Yately which has a thin north wall between its chancel and the north doorway which has Saxon window quite high up in centre of the length of wall. It has been readily visible since the church was burnt and rebuilt in the 70’s. S.W. of Odiham at least one of the Candover churches has a narrow chancel arch, round headed but plain which said to be indicative of a Saxon build. This is using the well known late Saxon small church at Bradford on Avon as a guide, a description is “small but showy”.”

Burh

A blacksmith specialising in ancient ironworking techniques and battle re-enactment, Ian Thackray, responded very strongly to the Rowhurst/Teazle Wood landscape because he was struck by it as ‘burh-like’. A ridge between two streams, with definite man-made defensive boundaries halfway down each bank, and the end of the ridgetop overlooking a village on flatter ground closer to the main river. He explained that the villagers, if threatened, would retreat to the high ground and a fortified place. He felt that the semi-basement might have been a structure designed to protect from attack, because of its stout construction.

Saxon/Norman tower

David Hartley of Surrey Archaeological Society has suggested that the semi-basement might be the bottom of a tower. Again, the square shape, the thick walls and extensive foundations imply that it was designed to support a substantial structure.

It is worth noting here that in one hidden part of the house, the flintwork continues right up to the second floor, and seems to be ‘jagged’, like a ruin – this might be worth investigating.

**In Domesday, Ralph Baingard (Baignard/Bainguard/Baingard/Baynard) holds one smallholding in Pachesham. This is the Ralph Baingard who built ‘Baynard’s Castle’ in London at the time – an ambitious builder. If the semi-basement is not associated with the church and vill, and is only that old (Norman), could this be his Pachesham home? Pachesham was divided into Pachesham Magna and the smaller and more fragmented Pachesham Parva, which appears to include part of Teazle Wood and the Rowhurst plot. If not the church lands held by Osbern de Ow in Domesday, could this Teazle Wood/Rowhurst plot be the single smallholding listed under the Lordship of Baingard? A tantalising entry in the 1200s suggests that Baingard may actually have lived at his Pachesham holding rather than just be attached to it by name as an absentee Lord – Levina Bayngard was raped by William Balemund in 1241. More than 150 years after Domesday, but surely the name is no coincidence? Was Levina a descendant of Ralph Baingard?

Medieval hall

All expert and amateur building historians have agreed that the 1346 wing of Rowhurst was once attached to an earlier building (probably a medieval hall), and was built on as a service wing. It has been re-set/raised, to make it more useful to the new brick house which dates to 1632. I’ll call the two wings (still standing) 1346W and 1632W.

So:

•Has the building 1346W was once attached to completely vanished, but was on the same site as the 1632W new house (i.e. its foundation would now be concealed underneath the 1632W house, and the semi-basement also only dates to 1632)?

•OR, is the building 1346W was once attached to still standing, and the semi-basement is the remaining lower part of the building to which the service wing was attached as an ‘improvement’ in 1346?

•OR, was 1346W originally attached to another building very close by on the same site (1346W hasn’t been dismantled; it has been raised or re-set, so we can perhaps assume that it hasn’t moved far at all, if it isn’t on its original footprint)?

Whose house was improved in 1346 by the addition of 1346W? In 1343, the word ‘Rowhurst’ (Anglo-Saxon meaning ‘Rough Wood’ - or my very long shot theory of ‘Owhurst’ – wood belonging to Ow; in Domesday, the land of the church of Leatherhead was held by Osbern de Ow [Eu in Normandy] – wishful thinking!) is listed alongside an entry for ‘a pigeon house’. This suggests that there was certainly a property on the site before the 1346 wing was constructed, and it also offers evidence of a place of some importance – pigeon houses / dovecotes were status symbols at the time, and were only permitted at castles, monasteries, churches and manor houses.

Medieval dovecote

One unexpected theory to emerge from 2016’s Heritage Open Days was the suggestion that we might be living in the dovecote.

I have noted crop marks in an aerial photograph in a field, just over 100 metres from Rowhurst, which seemed very like an excavation I had seen of a large circular dovecote.

With dovecotes in my mind ever since as circular structures, it hadn’t crossed my mind that we might be living in the dovecote, and that Rowhurst might actually be a house lying buried somewhere in our garden.

•Could 1346W have been added to turn the dovecote we know was standing in 1343 into a house, and later simply raised up a little when the house was improved by adding 1632W?

•OR, could 1346W have been built as a service wing to a medieval hall (say, on the building platform at the top of the garden or on the site of the large barn shown in 1842), with the dovecote nearby, and in 1632 – the large hall destroyed or abandoned, or indeed dismantled by the Pachesham vandalism of William Wimbledon well-documented in the late 1300s – someone decided to convert the sturdy dovecote remains into a house or hunting lodge, moving the surviving 1346W into position beside it and creating a substantial new house?

Wild, yes.

It is very difficult to imagine a dovecote built from scratch justifying the importation of flint and such sturdy and deep foundations. However, could ‘dovecote’ be a new use for an older building – a conversion of a strong, square building?

Certainly, there are some extraordinary examples of English and French huge, square dovecotes, with arches all round, or on three sides like those in Rowhurst’s semi-basement. The largest niche can even be explained – some dovecotes seem to have a deep covered recess with a stone basin, so that pigeons could bathe and drink without their droppings contaminating the water.

** The possible chronologies of 1346W need to be seen in the light of comments from dendrochonologist Andy Moir, who observed that the 1346 timber frame had been badly weathered on the inside - open to the elements and in situ (not dismantled) for a long time (he estimated a century or more). In 1348, two years after 1346W was constructed, the Black Death had a more vicious than usual impact on the Pachesham population (compared to neighbouring settlements such as Thorncroft, for example), and effectively wiped Pachesham off the map, permanently, as a significant village. In 1383, William Wimbledon, tenant of Pachesham’s lord, Sir Ivo Fitzwarren (Dick Whittington’s father-in-law) was accused of raiding the Pachesham manor buildings for their timber (this primarily relates to ‘The Mounts’ at this time, but were other buildings nearby – like Rowhurst and its dovecote - affected? We do know that ‘a dovecote’ was on the list of buildings he took timber from), although there were almost certainly two dovecotes in Pachesham – one in Pachesham Magna, and the one listed alongside Rowhurst – a clue to the possible location of the Magna dovecote is a later name for a piece of land adjacent to Randalls Road – ‘Dovecote Close’. Oak was Surrey’s main crop, and the Black Death had wiped out he labourers and left oak-framed buildings empty. In the absence of men to cut down trees and surrounded by unoccupied buildings, it made sense and was common practice to dismantle timber frames and sell the wood.

So when did 1346W stand empty, without its roof, in order to become so weathered on the inside? The current roof timbers have the date 1481 carved into one of them – such dates were carved in this way at that time, so this date could be authentic.

•Perhaps when it was first constructed, it was never finished, and the Black Death meant that it never received its first intended roof.

•Perhaps in 1383, along with the hall it was attached to and the dovecote nearby, it stood unoccupied, and vulnerable to William Wimbledon’s greedy and deceitful timber pillage.

•Perhaps it survived intact until it slowly declined into the “ruinous condition” of Rowhurst in the 1700s, and that the weathering did not happen until then. This fits less neatly, however, with the 1481 date carved into the roof timbers, and the fact that the 1632 timber is not weathered, although that part of the house may not have lost its roof tiles. I would need Andy Moir to look again at the 1481-dated roof timbers and see whether those, too, are weathered in situ, in order to narrow the timescale down to the 1346-1481 period.

•Or, of course, another cause that we as yet know nothing about

Carolean undercroft

It is of course possible that the flint semi-basement is absolutely contemporary with the 1632 house above it, and, although eccentric, it was all brand new in 1632, apart from the re-set 1346W.

If it turns out to be this recent, I suspect that the semi-basement was always just that – a semi-basement/undercroft to serve the new house above it. It bears a striking resemblance to an undercroft in Guildford, but then this Guildford example dates to the late 13th century, so maybe this takes us right back to the theory that the older hall to which 1346W was attached is still very much standing as the semi-basement.

I am also slightly confused re. why a rural house with plenty of land would have an undercroft – I have usually seen them in town streets, where space was limited and the undercroft created a valuable extra level. Were they used for food storage because they were cooler, perhaps?

I am also unconvinced by the notion that the whole 1632 building was built in one go, from scratch – the semi-basement has the sense of being a ruin that someone has later made good – the flintwork is ragged along the tops of the walls within the semi-basement, and in many places has been repaired and built up with bricks. It just doesn’t look or feel like one coherent, new 1600s building; the niches have been tampered with; the doorways and arches bricked up.

Would the flint foundations of a 1600s house have been so substantial? Is it relevant that the walls above the foundations are approx. 24-30” thick (I read that Saxon walls were usually only 2’6” thick because they used very strong mortar compared to later builders).

Buildings of 1600 are usually longer and narrower, with more bays. 1632W is only two bays long, and strikingly square in shape, as already discussed.

It is also important to note that the floor levels inside the 1632 building have been changed – when, and why?

We have also found distinctive and clearly older bricks and tiles through a hole inside the semi-basement wall. How did these get here, unless they were from an earlier building on the same footprint, or from the roof of the building that the semi-basement had been part of before, assuming it existed before 1632 as I suspect?

Can I stick my neck out, and state that I believe that the semi-basement is NOT contemporary with the 1632 building above it? Whatever it was part of before, I feel certain that it existed before someone built it up – and added or raised 1346W - to create the new 1632 house.

I have failed to date to establish the owner of Rowhurst in 1632, which would be very helpful in understanding the chronology of the building and the reasons behind such a major re-build in 1632. The improvement shows signs of high status – an ornate beam, covered ceiling beams, a wig cupboard, etc. The word ‘Rowhurst’ seems to disappear from written records after 1418, when it was owned by Richard Wrenne, and it doesn’t reappear until 1712 when it is surrendered in lieu of payment of a debt from Robert Marshe to Robert Ragge. I have my own theory about 1632, which I am currently investigating further – a key player and Royalist called George Mynne lived nearby at Horton, and he is known for stashing gunpowder and iron in various places around the county at the start of the Civil War. Rowhurst in its 1632 form is very much like a hunting lodge (access to adjoining and extensive good hunting land, plenty of space for food storage/preparation/eating, sleep provision for just a very few high status people, a very large pond on arrival, by 1842 a very large barn which would accommodate plenty of horses/dogs/people) and it is located in a wider landscape that we know was later used for hunting by Prince Leopold I and the Surrey Union Hunt. Rumours of it being a Royal hunting lodge abound, but I have no substantial evidence of this; Charles I did love hunting in the more peaceful early years of his reign, and Rowhurst is 6 miles exactly due south of Hampton Court Palace and 5 miles south-east of Nonsuch Palace, with wooded land still forming a discernible ‘V’ from both palaces that ends at Teazle Wood/Rowhurst (see image below). We asked Simon Thurley to check in Hampton Court’s records, and the word ‘Rowhurst’ does not feature on first investigation. Did someone like George Mynne construct a hunting lodge to entertain his prestigious friends, and was Rowhurst later used as a hiding place for gunpowder, iron and perhaps even people? Lots to explore.**It is also important to explain that in 1948 there was a major gas explosion on the Rowhurst site – this did damage to the roof and to the wall beside what is now our front door (western side). I have photographs of the damage, which could confuse those inspecting the fabric of the building**